The Mirror Image of Joan Jonas

Curator Pieter Boons in conversation with Nefeli Skarmea

Joan Jonas is a significant pioneer in video and performance art. Some of her iconic performances from the 60s and 70s are being re-enacted in COME CLOSER. How is it that they still feel so powerfully contemporary? Curator Pieter Boons asked Nefeli Skarmea, Movement Director for the artist.

From dancer to Movement Director

Your practice is very diverse. You have worked in ballet and contemporary dance, you’re curating, you’re a Movement Director, and you’re involved in public programming: for Serpentine in the past, and now for Fondation Plaza in Geneva. How do you play all these overlapping roles at the same time?

I studied dance: first classical ballet, then contemporary dance. For about 15 years I worked as a dancer with different companies and independent choreographers. I had multiple experiences in both physical and scenic ways, performing in different types of work, from very physical and technical dance work to more theatrical or conceptual work.

Dancing made me move a lot: not only on stage but also from country to country, from place to place. I studied ballet in London, contemporary dance in Rotterdam, butoh in Paris, yoga in India... All these different experiences are now part of my body’s physical memory. I also had experiences which helped me understand theatricality and dramaturgy, as well as the actual production of choreographic work.

At a certain point in your career, you turned towards visual arts.

In 2011 I became interested in changing things in my career as a dancer. I wanted to return to school, to research and have time for reflection instead of constantly working on a demanding physical level which, I felt, perhaps slowed me down mentally. I had always been interested in visual art, so I started a part-time MA of Curatorial Studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, Leipzig, which was very close to Berlin, which was my base.

Those two years I had the opportunity to dive into the history of dance and exhibition-making from the 1950s, to research the parallel trajectories of dance and visual arts, and how this connected to the performative dance practices in the museum of the 1990s-2000. I was interested in how the performance space, its context and aesthetics developed, and which are the ways we perceive all this in one.

In the same period, you worked as a curator for Documenta, and you kept adding and combining professional roles.

Working for dOCUMENTA(13) in 2012, I specifically became interested in producing, coordinating and co-curating performative works in different contexts: in the museum, in the gallery and, typically, in non-theatrical spaces. Since then, I have worked at the Serpentine Gallery and at Art Night London, a one-night art festival presenting a variety of performance-based work, newly commissioned or already existing. Following that, I worked on the exhibition project Dance First Think Later in Geneva, focusing on the encounter between visual arts and dance. Today I work as a coordinator of cultural projects at the Fondation Plaza.

All these different roles are somehow connected somehow. I don’t perform anymore, but I still carry in my body all the experiences I lived through. Through my experience as a dancer, I comprehend what happens on stage, and through my studies and experience in coordinating, organizing and programming, I see what’s needed behind the stage. In a way, the one feeds the other. I am very aware of the needs of production, especially with movement practices and in connection to rehearsals, staging and dramaturgy. I can grasp how the dancers feel, as I experienced it all firsthand. Now, I learn more about communicating about the works, and organizing them in the long term.

Collaborating with artists seems to be a red thread through your practice: as a dancer, as a producer and as a programmer. How does that sound to you?

Collaboration is indeed the core of my work. The work with choreographers is collaborative, as is the work with peer dancers. Producing and realizing artistic work is always in liaison and collaboration with the artist. This steady and continuous chain of potential collaboration remains the most interesting part of the work.

It feels like switching from one type of creation, where I was really part of the work itself, to another where I’m less present, but still part of it, and still participating in the realization of an artistic vision. From this side, I get a better overview in a way… As a dancer, my input to the work was more creative. Now, it feels more like accompanying the artist, their work.

Translating between performance and visual arts

You’re a Movement Director, which to me is a very inspiring word. I had never heard of it before. How would you describe it?

This term has been adopted to describe the kind of work I do, although it can mean different responsibilities in different institutions. In my understanding, a Movement Director is the person who directs movement practitioners and, in my case, plays the role of the translator between the language of visual arts and movement vocabulary. Between a visual artist for example and the dancers or performers they use in a specific work.

Several visual artists, whose practice has not necessarily been associated with live art, became interested in incorporating the performative aspect in their work. For example, Martin Creed, Cally Spooner, Megan Rooney, Anthea Hamilton, and many many others in the recent years. Artists like them, shifting from sculpture, painting, installation, video, or photography, wish to work with movement and with people moving, but do not always have all the necessary tools and the necessary vocabulary to explain and transmit their ideas to dance practitioners. So, I’m somehow the translator between the two.

That brings us to my work with Joan Jonas. For the restaging of her historical performances, created in the 60s and 70s, I suggested some adaptations and updates of the spatial arrangements, movements, and their transitions to Joan. Performance has evolved from those early years, and so I saw myself translating what I thought was the spirit of the work, the intentions behind the different scenes and movements, to today’s contemporary dance artists.

Through your experience as a dancer, you can imagine what dancers feel, do and need. From the perspective of the visual artist, you jump to the performer. But you also translate works towards the institution, the location, or the context of the exhibition, which is an extra translation.

I’m aware of that. I don’t see myself as a choreographer, and I’m not a dramaturge either. Perhaps what I do is set between expanded choreographic practices and spatial curation! My diverse experiences allow me some agency, even if this happens very intuitive. Such as to propose, for instance, Mirror Check to be included in the show at Middelheim Museum, or to suggest changing the performance space if the initial placement doesn’t feel right.

Working with Joan Jonas

In 2012 you met Joan Jonas during dOCUMENTA in Kassel. How did your collaboration start?

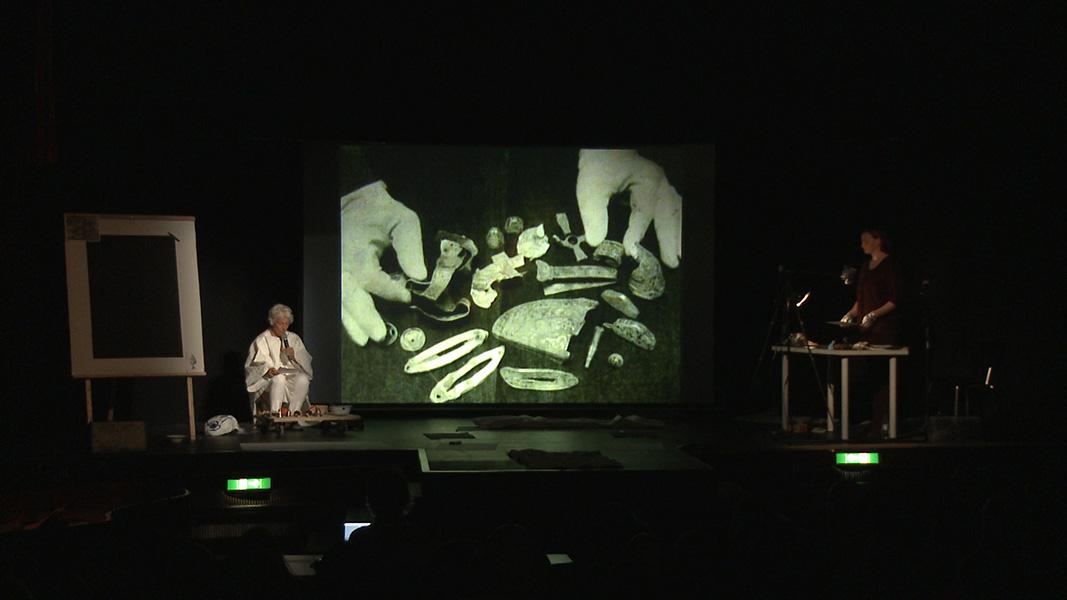

When I first met Joan, she was rehearsing the work Reanimation, newly commissioned by dOCUMENTA(13). She performed herself, together with the jazz pianist Jason Moran, on the stage of a disused cinema on a central square of downtown Kassel. When I was appointed to this project, I entered the rehearsal, introducing myself and asking Joan how I could be of assistance. She replied: “Could you stand on stage and pretend to be me? I can never see myself doing the movements.” I had already watched some of the rehearsal, so I knew what I was supposed to do, so I jumped on stage and took her place. She went down to the empty auditorium, she watched and said: “well, now I understand!”

She started asking me for dramaturgical advice, how long should one scene be, where should she stand exactly to be better perceived by the public, what does this movement look like? I therefore became an “outside eye” for her performance and Joan seemed to like that and appreciated my feedback. It seemed that she had not often received criticism as to the detail or the quality of her movements.

For me, her artistic expression was somewhat completely new. Joan is an extraordinary person. She manages to create seamless narratives by using many different means and media. I had never imagined that something like that was possible. In Reanimation she combined video recordings, static or moving images projected from overhead projectors or video cameras static, casting live closed-circuit footage on a huge screen, paintings happening on the spot, objects telling stories, movements being danced. Apart from the extraordinary themes played on the piano, she improvised sounds and tunes with small and large instruments, stones, rattles, and other objects she had collected on her travels. The performance was epic and I got immediately hooked.

In 2018, your collaboration strengthened during the preparation of her big show at the Tate. Could you talk more about that?

In preparation of her exhibition at Tate Modern in 2018, where she was encouraged to revisit and present some of her early performances from the late 60s and early 70s, Joan invited me to assist her. I lived in London at the time, which was practical. While she was installing the exhibition, she initially asked me to help her reconfigure her performance Mirror Piece. However, no video documentation existed from the original iteration of this work, apart from a rough version she had created a few years back at the Guggenheim.

We watched this video from 2010, as well as a score Joan had created: 15 little mirrors beautifully drawn on an A4 sheet of paper, depicting them in different configurations and following a specific order. I had never seen the performance live, so I studied this score, I looked through many photographs and read catalogue texts written about the original performance. Joan also described what was happening in the piece as she remembered it.

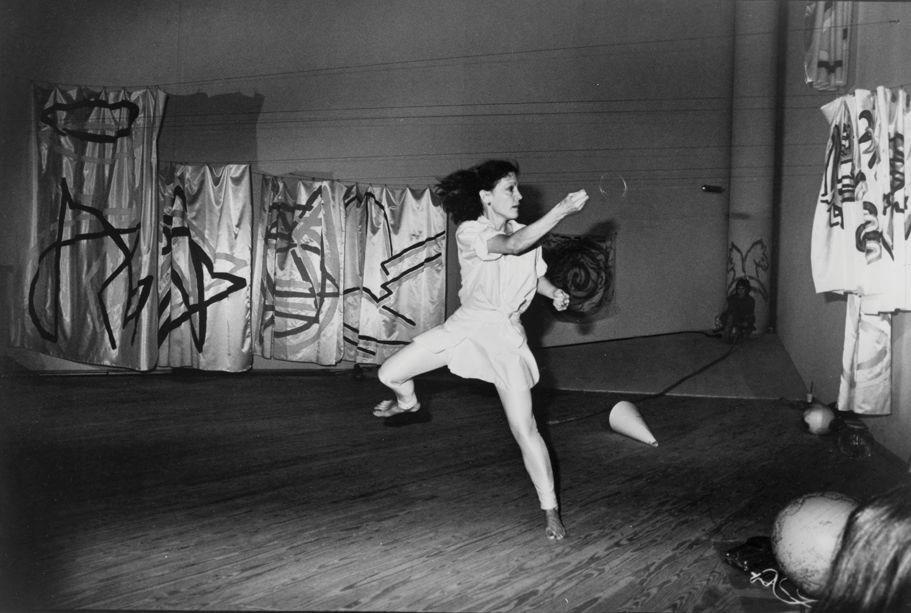

What is tricky about the score, is that it illustrates the different positions of the mirrors in different scenes without explaining the transitions between them. How do we get from one configuration to the next? Joan explained that this should be done in the most functional and direct way and so I started re-composing the choreography. In Mirror Piece the performers carry heavy, full body sized mirrors in space. The mirrors face the public and as they move the constantly fragment and modify everything that is reflected in them: their surroundings, the image of the audience and of course the bodies that carry them.

For the Tate Modern exhibition, we reconfigured two more performance pieces: Mirror Check and Delay Delay. The latter was performed outdoors on two opposite shores of the river Thames during low tide. That was quite challenging in terms of coordinating: tide times shifted from one day to the next and the surface available to the performers changed as well. The spacing of the work had to be adapted from day to day.

What was for you the most exciting part of these collaborations?

You know, today we can see these works in history books and artists’ catalogues. I love watching these performances becoming alive, some 50 years later! That was incredible. What I also enjoy is working with an artist who knows exactly what they want. The way Joan communicates about the work is very clear and straightforward. Every time I had a doubt about recreating a part of a scene, or a configuration on stage, she immediately had an answer. This enabled an excellent collaboration between us, very joyous and fulfilling.

Iconic performances in COME CLOSER

Let’s talk about Mirror Piece and Mirror Check, the two performances we’ll be presenting in COME CLOSER. Why do you think they have become so iconic?

The mirror was and is an everyday object, but it is also kind of mysterious. It multiplies the human existence and its surroundings. Today, we have another connection to the mirror in our everyday lives due to the “black mirrors” we carry around all the time.

The idea of the mirror in Joan’s work came from the writings of Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentinian author, whose books were just being translated into English in the sixties. His work attracted a lot of attention in the art world, and Joan too, found his short stories Labyrinths very fascinating. She collected different excerpts from these stories referring to mirrors and recited them wearing a black dress with mirrors stuck on it. This was her very first performance which developed into the Mirror Pieces. The mirror was her very first prop and reappears very often in her work.

Back in the 60s, there were no mobile phones of course. The work was perceived differently. Today, selfie culture makes us see the mirror in a different way. People are constantly confronted with their image in the world, filmed, shared, communicated, posted on social media. When the performers walk with mirrors on stage the audience is confronted with the image of itself, watching. The moment where this relationship establishes between the audience, the performance space and the happening through the reflections in the mirrors is very engaging, possibly a little uncomfortable, and thought provoking.

No matter where the mirrors are, near or far, they always tempt us to look at ourselves, search for our image, in a somewhat narcissistic manner. We typically examine the reflection of the others too, while the performers’ movements invite our gaze to zoom in and out of what is happening on stage. These notions and ideas are very interesting and remain current. One could claim that these works have become iconic because they these questions are contemporary and rather timeless.

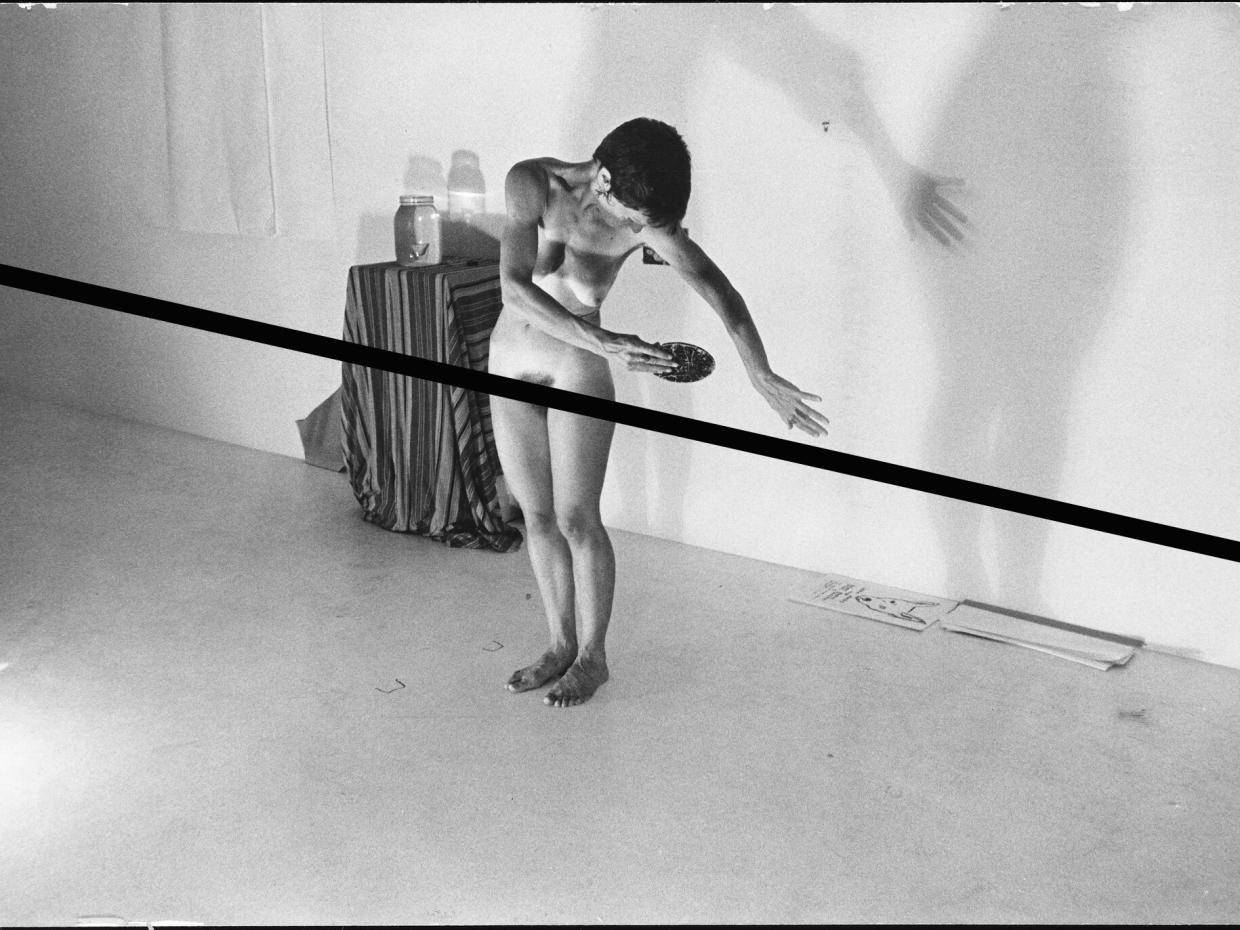

Mirror Check plays with mirrors as well, but in another way.

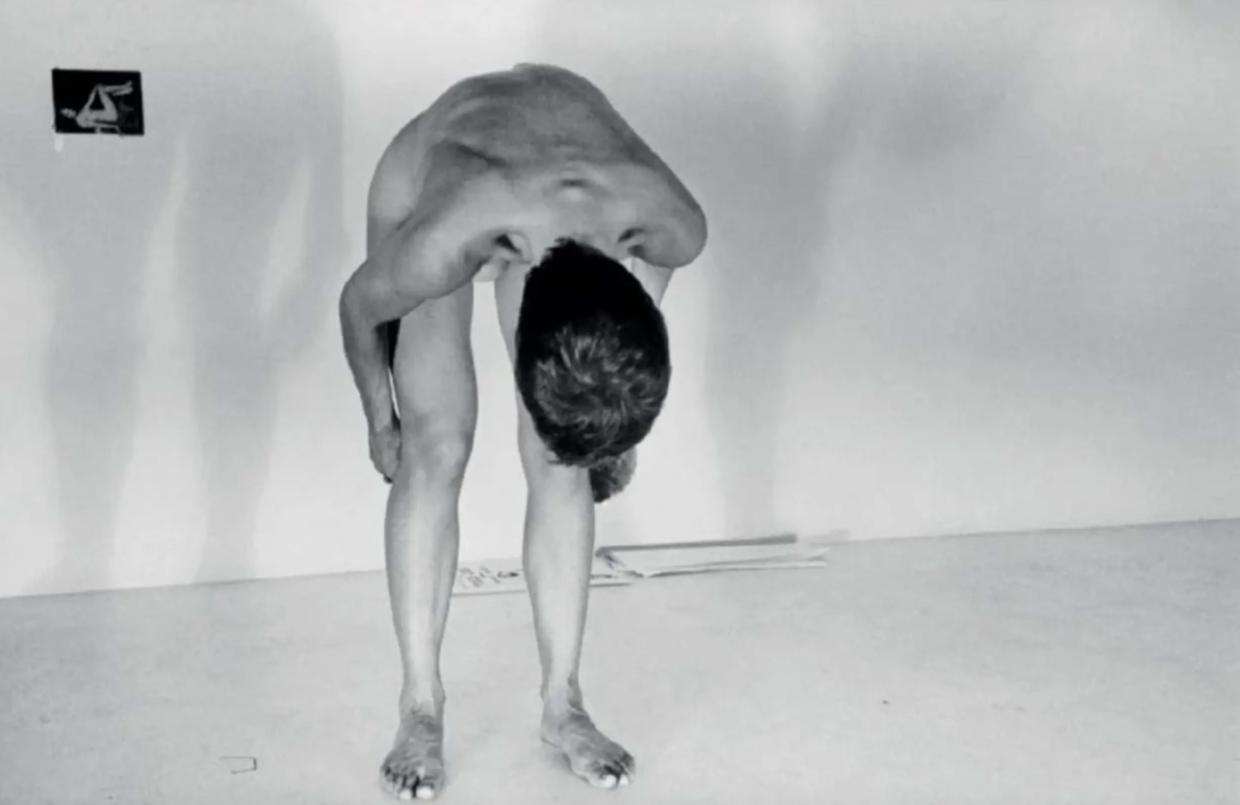

In Mirror Piece we see everything in large mirrors moved by the performers: the audience, the performers, the surrounding, everything can enter in these reflective surfaces. Mirror Check is the opposite. We cannot see anything in the small round mirror held by the performer. The performer, a naked, female body, uses it to visually scan each part of their body. Even though we understand what the performer might be seeing, we do not literally see this same image; the mirror offers a very private view. This work raises quite fundamental questions about the female body, its image, emancipation, and nudity.

I feel that Mirror Piece and Mirror Check are compatible and address similar questions in different ways and this is why I took the liberty to propose presenting both at Middelheim Museum.

In this new context, a sculpture park with a lot of nude bodies around, the performances get an extra layer.

The art park reflects the way the female body has been viewed and reflected on in the arts and over the centuries. Joan shifting towards performance in the 60s coincides with the unfolding of the feminist movement, women’s emancipation and of sexual revolution. Miniskirts were a thing. Presenting these works in all new contexts provides space for reflection on these issues – still pertinent today.

Bringing indoor performances outdoors

In COME CLOSER we present outdoor versions of indoor work. For the museum, it’s really challenging to do this. You don’t only have to think about the materiality of the works, but also what it means to bring a work outdoors. For Joan bringing the indoor work outdoor changes them into a new work. How do you deal with change in your collaborations with Joan?

As a Movement Director in charge of these early performance works, the most obvious change that needs to happen in each presentation is the cast. It’s important for us to work with a local cast, with artists and practitioners from the local art communities. Then there’s also the adaptation to each new space which for me is a big part of the work.

However, there are also certain elements that are fixed. When Mirror Piece at Tate Modern was performed, Joan was very pleased with its reconfiguration. We have therefore used this version as a definite choreography. The video documentation is also now used for the transmission of the piece.

Still, there are always shifts in timing and spacing, which depend on the location but also on performers’ inner timings while moving. This changes from place to place from day to day and this is an element that keeps the work alive, invigorating, collaborative in situ and in the moment.

The fact that Joan has been explicit about the choreography being set, makes it easier for me to adapt everything else: the spacing in a new location, the different casts, the indoor or outdoor versions. There is a little space for improvisation, but the key moments are fixed.

COME CLOSER

It's the same for Joan’s installation works in COME CLOSER. There are fixed references, but change is possible because you know there’s a base where you can start working from. That’s a very elegant way how possibilities can grow. How do you look at the presented selection of sculptures, and the thread between them?

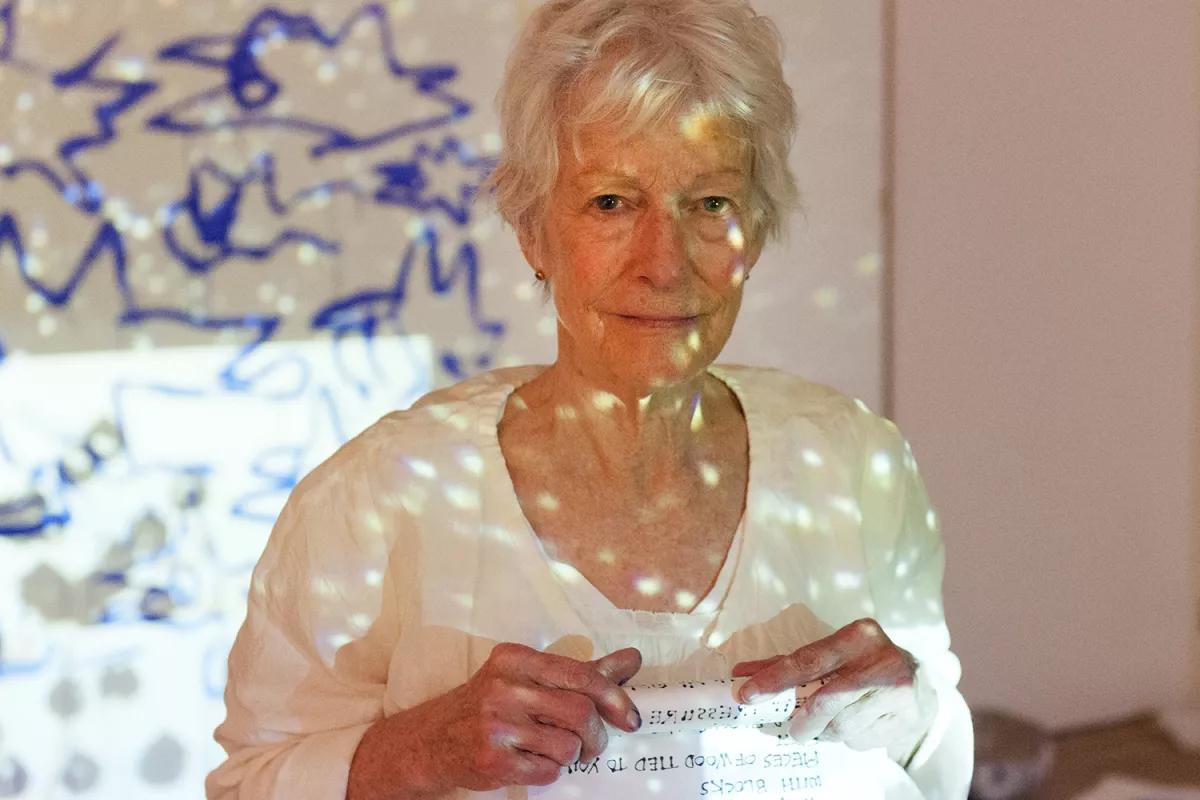

I find the curation of the works is outstanding – congratulations Pieter! Joan’s expression has an incredible breadth, as it spans many media. The fact that you can show video, sculpture, and installation alongside the two performances, or the other way around, displays the richness and plurality of her oeuvre, which is wonderful.

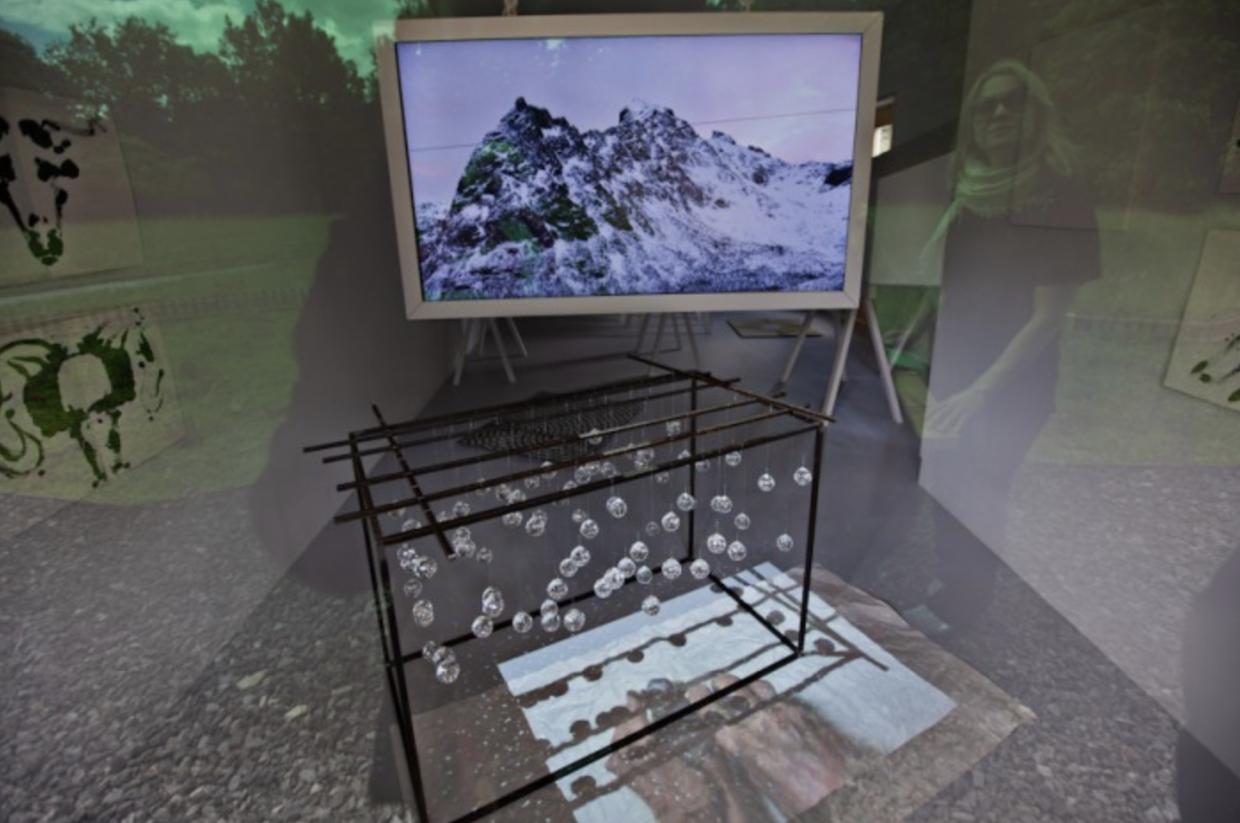

For instance, in the video work Good Night, Good Morning presented as part of the new outdoor version of My New Theatre VI at Middelheim Museum, Joan speaks to the camera and records herself. This, if you like, is an extension of what a mirror does, repositioned in time. She uses technology to see herself and record her image.

This work reveals the evolution from one medium to another and how Joan moves from performance to video. This might have been a simple and organic transition for Joan but history proves it was a big step in the arts!

6 Feet (measuring device) is interesting again, because she employs a more minimal expression about the very particular isolation experience people had during the corona pandemic, where social distancing of six feet had to be maintained. For me it relates again to bodies in space. Their connection or remoteness. Measured with a branch from a tree, which could have been from the Middelheim Museum art park itself.

For me, as a curator, it was very challenging to bring the Mirror Room III Outdoor (1968/2024) together. It’s the space where a lot of performances originally arose or happened. There’s the hoop, one of the first videos of people experimenting with mirrors and bodies… This outdoor area is a reflection on the landscape, which I think we need to do urgently. There are a lot of possible connections, possible ways of coming closer. What does COME CLOSER, the project’s title, mean to you?

I have to think of the opportunity I am given to work and connect with the local community of artists. We enter Joan’s universe together to recreate these performances and this bring us and brings them together. Some performers may have met each other, studied together, or collaborated previously. The idea that we invite people from different movement and practice backgrounds to participate, also allows these disciplines to come closer, encouraging new exchanges and encounters. Quite a unique configuration is created via these groundbreaking, historical works.

Apart from that, from a curatorial perspective, the idea of bringing sculpture and performance closer, is very exciting. It recalibrates the way we look at art, the way we question ourselves and the human condition and of course the way we connect to nature, as we are fortunate enough to be in a vast public park. COME CLOSER makes me also think that, through the works of Joan and of the other artists, the exhibition questions the proximity of human beings: do they enjoy or detest coming closer?

Lastly, I feel grateful to be able to bring this, rather large, group of 15 performers together. We do come closer for the duration of the project – performing in silence creates a state of heightened awareness, especially amongst the performers, of a certain tension, a very special togetherness.

What a nice end. Thank you very much for this conversation.

Pieter Boons, Antwerp, 24/05/2024

Short bio Nefeli Skarmea

Drawing from her professional experience in contemporary dance, Nefeli Skarmea has advised visual artists working with performances, such as Martin Creed, Cally Spooner, and Megan Rooney. After completing her additional Masters in Cultures of the Curatorial, Nefeli worked at institutions including dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, the Serpentine Galleries' Public Programs, and Art Night London.

Since 2018, she has been serving as Movement Director for the restaging of Joan Jonas' performances. Today, she also acts as coordinator for the cultural program of the Plaza Foundation in Geneva.